An organisation’s success, reputation and long term sustainability depends on its stakeholders and how they perceive the organisation. The way the organisation interacts (or is perceived to interact) with its stakeholders builds its reputation and its customer base. But customers belong to communities and it’s the broader community that grants the ‘social licence’ needed for the organisation to operate long-term. And, because no one and nothing is ever perfect, things will go wrong from time to time requiring action to protect the organisation’s reputation and its social licence.

The objective of this post is to:

- Put all (or most) of the different mechanisms used by organisations to engage with stakeholders into perspective; and

- Emphasise the message that authentic and effective stakeholder/community engagement needs an organisation-wide coordinated approach that is governed from the very top levels of management.

The Stakeholder Engagement Spectrum

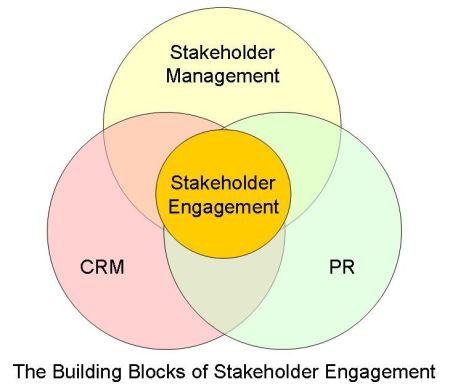

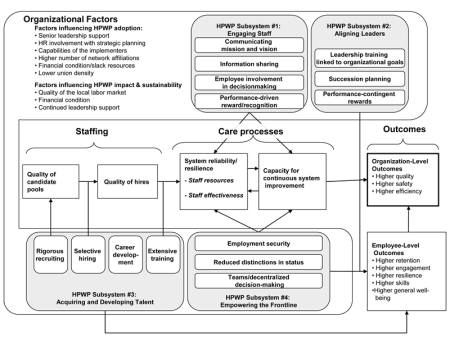

The Organisational Core

The characteristics of the organisation are always at the centre of every stakeholder relationship[1]. The way your organisation is structured, its ethics, characteristics, systems, and services, underpin how its stakeholder community will ultimately perceive the business. The key to successful stakeholder engagement is in part the way the organisation is structured and operated, and in part being authentic and realistic in the way various aspects of stakeholder communication and engagement are used. If your business is a low-cost, low service, bulk supplier don’t pretend to be an upmarket high service organisation. Many people are more than happy to shop at retail outlets such as Walmart and Aldi, attracted by price and simplicity; others prefer the higher levels of service and higher prices from more upmarket department stores. The art of stakeholder engagement is to maximise the appeal and perceptions of the organisation as it is – not to mask reality with a pretence of being something else.

However, poorly governed unethical organisations will always ultimately fail regardless of their stakeholder engagement effort; you can’t build an effective long-term relationship on unsound foundations.

The 8 Aspects of the Stakeholder Engagement Spectrum

The eight aspects of stakeholder engagement highlighted above are all well defined in various publications; the way they are used in this post is briefly set out below:

PR: Public Relations – The actions taken by an organisation to develop and maintain a favourable public image. PR is a strategic communication process that builds mutually beneficial relationships between the organisation and its stakeholders. The core element of PR is push communication; it is a proactive process controlled by the organisation, broadcasting information to a wide community to influence attitudes.

Advertising – The activity production and placing of advertisements for products or services. The purpose of each advertisement is to announce or praise a product (goods, service, concept, etc.) in some public medium of communication in order to induce people to buy, use it, or take some other action desired by the advertiser. The difference between PR and Advertising is that PR largely focuses on creating or influencing attitudes and perceptions whereas advertising focuses on some form of ‘call to action’.

CRM: Customer Relationship Management – Refers to the practices, strategies, and technologies that organisations use to manage and analyse customer interactions and customer data throughout the customer lifecycle. The goal of CSR is to improve the organisation’s relationship with each customer, assisting in customer retention, and driving sales growth. Good CRM systems make it easy for people to do business with you.

Issues Management[2] – The process of identifying and resolving issues. Effective issues management needs a pre-planned process for dealing with unexpected occurrences that will negatively impact the organisation if they are not resolved. The scope of this concept ranges from ‘crisis management’ where the magnitude of the issue could destroy the organisation (and the most senior management take an active role) through to empowering staff to deal with relatively minor customer complaints. The key to effective issue management is resolving the issue to the satisfaction of the affected stakeholders. This requires effective systems and preplanning – you don’t know what the next issue will be, but you can be sure there will be one.

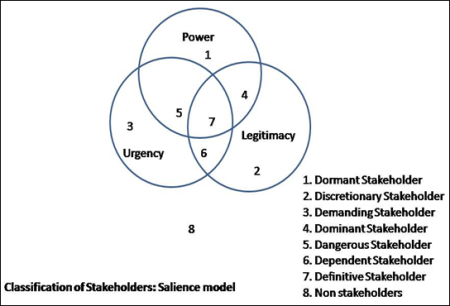

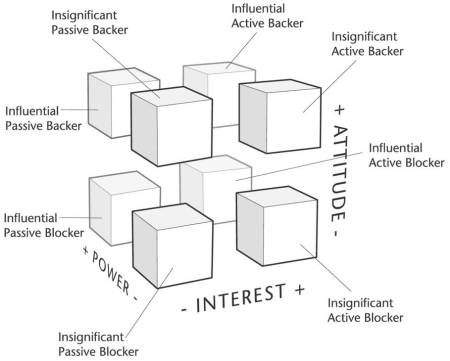

Stakeholder Management Initiatives[3] – this is the area where most of my work is focused; managing the expectations of, and relationships with, the stakeholder community surrounding an organisational activity, initiative, or project. Most business initiatives and projects have a high potential to affect a range of stakeholders both positively and negatively (and frequently both at different times). How these relationships are managed affects not only the ability of the organisation to deliver its initiative or project successfully, but also the overall perception of the organisation in the minds of the wider stakeholder community.

Business Intelligence & Environment Scanning – BI and other forms of environmental scanning looking at attitudes, trends, behaviours, and other factors in the wider stakeholder community. They are a key emerging element in the overall approach to stakeholder engagement used by proactive organisations. This is very much the space of ‘big data’ and data mining. Much of the collection of data can be automated and ‘hidden’ from view. The challenge is making sure the information collected is legal (privacy legislation is an important consideration), accurate, relevant, and complete; then asking the ‘right questions’ using various data mining tools. As with any intelligence gathering process, obtaining the data is the easy part of the equation; the real skill lies in developing, validating and interpreting the data to create information that can be used to produce valuable insights.

Social Networks – The ubiquitous, widespread, and diverse nature of social networks ranging from Facebook to personal interaction down the pub can easily outweigh all of the organisation’s efforts to create a positive image using PR, advertising and the other ‘controlled’ functions discussed above. The organisation’s staff and its immediate stakeholders literally have millions of connections and interconnections to other stakeholders. Most of these connections are unseen, and the environment cannot be controlled. The best any organisation can hope to achieve in this relatively new communication environment is to plant seeds and seek to have some influence. Seeding ideas and concepts into the ‘Twittersphere’ may result in a concept being taken up and ‘going viral’, more commonly the seed simply fails to germinate. Conversely identifying negative trends and issues early, particularly if they are false, is critically important and where possible these negative influences should be countered but given the nature of the environment this is a very difficult feat to achieve. Smart organisations recognise that their staff, customers, contractors, and suppliers all engage in this space and through other effective communication channels can influence how these people respond to opportunities and issues affecting the organisation.

CSR: Corporate Social Responsibility[4] – CSR completes the circle and brings it back towards the concept of PR. CSR contributes to sustainable development by delivering economic, social and environmental benefits for all stakeholders. ISO 26000 Guidance Standard on Social Responsibility, defines social responsibility (ie, CSR) as follows:

Social responsibility is the responsibility of an organisation for the impacts of its decisions and activities on society and the environment, through transparent and ethical behaviour that:

– Contributes to sustainable development, including the health and the welfare of society

– Takes into account the expectations of stakeholders

– Is in compliance with applicable law and consistent with international norms of behaviour, and

– Is integrated throughout the organization and practised in its relationships.

The key difference between CSR and PR is that CSR actually involves doing things both within the organisation and within the wider community, whereas PR focuses on telling people things.

Applying the Stakeholder Engagement Spectrum

The various aspects of stakeholder engagement spectrum combined together to create the organisation’s reputation, engage communities, build customers, and when necessary protect the organisation’s reputation. The key combinations are set out below:

Reputation Creation: The key components needed to create and maintain a desirable reputation start with CSR and work clockwise through the spectrum to CRM.

Community Engagement: The key components needed to effectively engage the wider community are focused on CSR but includes the elements moving anti-clockwise from CSR through to Issues Management.

Building Customers: The elements needed to build and retain customers start with PR and work clockwise through the spectrum to Issues Management.

Protecting Your Reputation: Finally protecting the organisation’s reputation is focused around Issues Management, but includes elements of CRM and continues clockwise through to Environment Scanning. In addition, many of the ‘push’ elements in the spectrum may be used as tools to help manage issues and protect the reputation of the organisation including PR and advertising.

Conclusion

The ‘stakeholder engagement spectrum’ above is deliberately drawn in a circle surrounding the organisational core, because all of the different aspects interrelate, many overlap, and they all build on each other. The governance challenge facing many organisations is breaking down the traditional barriers between functional areas such as advertising, PR and CRM/sales, so that the entire organisation’s approach to its stakeholders is coordinated, authentic and effective.

________________

[1] See more on Ed Freeman’ stakeholder theory at: https://mosaicprojects.wordpress.com/2014/07/11/understanding-stakeholder-theory/

[2] For more on issues management see: https://mosaicprojects.com.au/WhitePapers/WP1089_Issues_Management.pdf

[3] For more on stakeholder management see: https://mosaicprojects.com.au/Stakeholder_Circle.html

[4] For more on CSR see: https://mosaicprojects.wordpress.com/tag/corporate-social-responsibility/

Posted by stakeholdermanagement

Posted by stakeholdermanagement