Organisational change seems to be far more difficult in some organisations than others – this blog will suggest the reason and a possible solution! But before looking at these concepts, let’s lay out the basics:

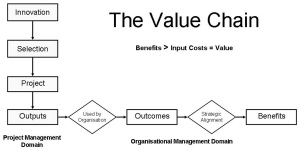

- The concept of using projects to enable the creation of value is fairly well accepted, the value creation chain starts will innovative ideas and finishes when the benefits are realised and value is created (read more on Benefits and Value):

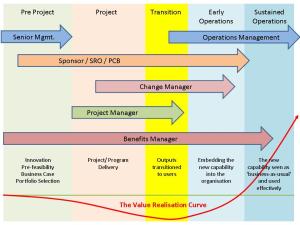

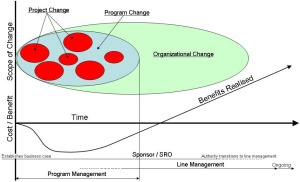

- The effect of the ‘chain’ means that when you have got to the end of the project (or program) all that has happened is you’ve spent money, benefits and value come later and need a ‘team effort’ from all levels of management to be maximised (read more on Benefits Management).

- Consequently the key to realising the benefits and maximising value is effective organisational change (read more on organisational change)

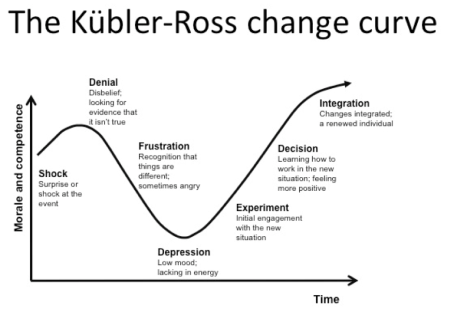

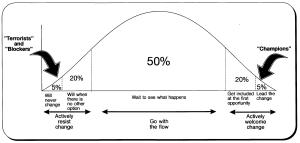

- And the basic concepts of organisational change have been defined by numerous authorities from the perspective of stakeholder attitudes:

And the rate of adoption of the change:

- The concepts are documents in a range of references including

– PMI’s Managing Change in Organisations – a practice guide

– APMG International’s Managing Benefits

But none of these well established concepts really explain why some organisations are open to change and others are not; the question this post is focused on.

One insight that helps explain why some organisational cultures are resistant to change and others more open to change is discussed in an interesting paper: Darwin’s invisible hand: Market competition, evolution and the firm (Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization: Dominic D.P. Johnson, Michael E. Price, Mark Van Vugt).

The paper suggest that the Darwinian view that competition among firms reflects the ruthless logic of ‘selection of the fittest’, where the free market is a struggle for survival in which successful firms survive and unsuccessful ones die, is only partially correct.

The application of Darwinian selection to competition among firms (as opposed to among individuals) invokes group selection, which requires altruism and the suppression of individual self-interest to the benefit of the ‘greater good’ of the group and the advancement of the firm.

This effect can be achieved in circumstances where the organisation is lead by a charismatic leader who can inspire the members of the organisation to sacrifice their short-term self interest to the ‘greater good’. Or when the members of the organisation are either inspired by the organisation’s mission (eg, committed workers in many aid organisations) or feel the organisation is threatened and that sacrificing their short-term best interests to help the organisation survive is essential for everyone’s long term good. These types of situation create the same effect as a ‘high performance team’ – individual team members ‘play for the team’ ahead of any selfish interests.

If any or all of these factors are in play, and are appreciated by the individuals that make up the organisation, the ability to implement change is significantly increased (provided the change can be seen to contribute to the mutual good / mutual survival).

However, if the members of the organisation feel the organisation is fundamentally impregnable, there’s no threat (or common enemy) and no inspiring mission, a completely different dynamic come into play. The competition and Darwinian ‘survival of the fittest’ plays out at the individual level. What matters most is how the proposed change will influence existing power structures and networks. To most people the change is likely to be perceived as a threat; they know what the status quo is but can only imagine the future state after the change and will generally imagine the worst case due to our innate biases. And consequently the change has to be resisted – the normal ‘change management challenge’.

These ideas seem to make sense of our general observations:

- Change seems easier in small or medium sized organisations because the members of the organisation see their self-interest is closely aligned to the success of the organisation

- Some inspirational organisations seem to adapt to change easily, 3M and Apple spring to mind, a combination of inspirational leadership and a strongly believed mission to create new things.

- However, in many established large organisations in both the public and private domains, the link between the individuals well-being and the organisations well-being is less clear and entrenched self-interest takes over. The well known ‘office politics’.

So how can a change agent overcome the entrenched inertia and covert opposition experienced in the change resistant organisation? Short of generating a massive crisis (eg, the General Motors reorganisation) most change initiative will fail if they are not carefully managed over a sustained period.

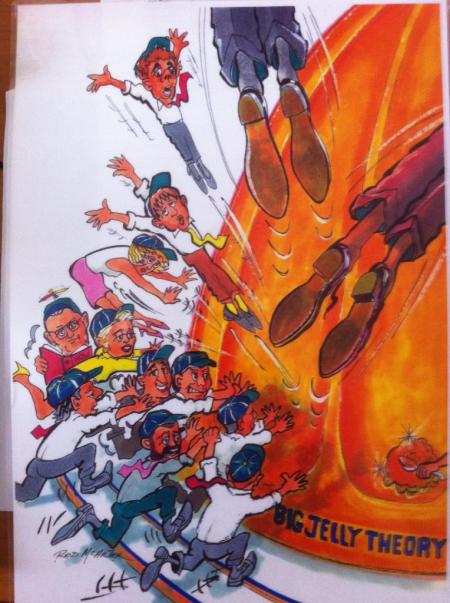

One idea that can be used in these circumstances is Paul Finnerty’s Big Jelly Theory.

The Big Jelly Theory, postulates that large or very large organisations are extremely difficult to change, but it is not impossible to do so. The problems change agents often encounter are caused by the approach chosen to effect the required organisational changes.

Paul’s theory is that if you throw yourself and your team members, 100% mentally and physically at the organisation in an attempt to force it to change at best the organisation will giver a little shiver, momentarily, like a giant jelly, and then immediately return to it’s pre-existing shape and carry on with business as usual as though nothing has happened.

The theory postulates that the only effective way, to change or realign an organisation, is to metaphorically issue each of the change team members with spoons. The team members then use these spoons, to sculpt away at the big jelly, and in doing so changing the organisations shape, to whatever has strategically been deemed as more desirable, for the future.

In other words whilst effort and enthusiasm are important, in making or reshaping organisational changes, they are very often ineffective, when used alone. Whereas the spoon approach, whilst often time consuming, yields discernible result almost from the start.

This is in effect the Kaizen Way – great change is made through small steps. Rooted in the two thousand-year-old wisdom of the Tao Te Ching, Kaizen is the art of making great and lasting change through small, steady increments. Dr. Robert Maurer, a psychologist on the staff at the UCLA recommends:

1. Ask small questions.

2. Think small thoughts

3. Take small actions.

4. Solve small problems

5. Bestow small rewards.

6. Identify small moments of success.

Provided you have the overarching ‘grand vision’ to coordinate and align the small changes, the results can be amazing!!!! It just needs time, perseverance and really effective long-term stakeholder management which is where tools like the Stakeholder Circle® come into play.

[…] Why Organisational Change Is So Difficult […]

[…] Why organisational change can be difficult | Stakeholder … […]

[…] Why organisational change can be difficult | Stakeholder Management’s Blog. […]

[…] Source: stakeholdermanagement.wordpress.com […]

Some really interesting perspectives here, thank you.

It is all about appropriate balance, and some of the discussion appears to have changed the emphasis of the article.

Delivering value incrementally through a programme is ideal but should never become the driver. IT users, for example are now besieged (strong word I know) with constant updates, update after update every time they switch on their systems. Is this because we are too focussed on delivering something too soon (a risk Agile seems to ignore)

Also Kaizan, this all stems from the Lean Principles developed (largely) by Toyota and the Japanese. But read what Toyota do, and you will discover excellent plans for change that are tested, challenged, re-tested and re-challenged before rapid implementation.

Just my view of course

[…] Why Organisational Change Can Be Difficult (Lynda Bourne – Stakeholder Management) […]

Reblogged this on PMmetrics.